This blog focuses on my scholarship in my five research projects: learning assistance and equity programs, student peer study group programs, learning technologies, Universal Design for Learning, and history simulations. And occasional observations about life.

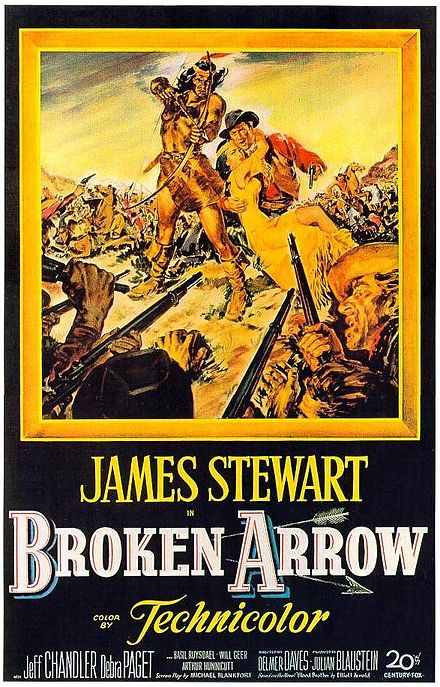

"Broken Arrow" starring Jimmy Stewart and Jeff Chandler

The movie "Broken Arrow" was one of the first Hollywood films to provide a sympathetic view of the Native Americans. While highly imperfect, especially since Jeff Chandler played the role of the great Native American leader Cochise of the Apache tribe, it was groundbreaking in 1950 to reveal the violation of the Indians by the U.S. Government and the honor displayed within the tribe. After his time flying bombers in WWII against Germany, Jimmy Stewart's movie roles were less the idealistic ones from before the war (It's a Wonderful Life, etc>) and more gritty and realistic. this movie is a good example of his change of movie roles. I suggest you read the Wikipedia entry about this 1950 film by clicking on this link. While imperfect, I think you would enjoy this movie. Click the red button to start the movie.

The movie "Broken Arrow" was one of the first Hollywood films to provide a sympathetic view of the Native Americans. While highly imperfect, especially since Jeff Chandler played the role of the great Native American leader Cochise of the Apache tribe, it was groundbreaking in 1950 to reveal the violation of the Indians by the U.S. Government and the honor displayed within the tribe. After his time flying bombers in WWII against Germany, Jimmy Stewart's movie roles were less the idealistic ones from before the war (It's a Wonderful Life, etc>) and more gritty and realistic. this movie is a good example of his change of movie roles. I suggest you read the Wikipedia entry about this 1950 film by clicking on this link. While imperfect, I think you would enjoy this movie. Click the red button to start the movie.

Recommended History Podcasts

Click on this link to read a handout I prepared on podcasts related to history that I have subscribed for free through the iTunes Podcast service. I do not claim to listen to all the episodes obviously. However, I go through and select episodes of particular interest. I do make sure to download all episodes and went into the settings for my podcasts so that past episodes that are played do not automatically become deleted. Apple does that by default so that your hard drive is not becoming overloaded with media that you may not ever play again. While this is not a big issue with most audio podcasts, some video podcasts have enormous file sizes simply because it takes more room to provide them. Several of my personal favorites are the video podcasts from NASA. If you subscribe to the HD quality video podcasts, individual episodes can exceed 200 MB. Fortunately, most recent personal computers are increasingly providing standard hard drives of a terabyte or more. As a history teacher, I like to keep all the episodes for future reference. I think of them as my personal library like some people like to collect movie DVDs.

In 2013, Apple reported that a billion people world-wide have subscribed to a quarter-million podcasts in 100 languages, and that more than eight million episodes have been published in the iTunes Store thus far. Searching for podcasts through the iTunes Store can be a challenge. The following list is merely a sample of the history podcasts. They were enough of an interest to me to subscribe.

Many of the podcast shows can be subscribed to through iTunes, Google Play Store, and other mediasubscription services. Since I am most familiar with the Apple media ecosystem, the following podcasts are available through the Apple iTunes store. These are identified by the iTunes name appearing in the title line for the podcast. Formal subscription to the podcasts are not required for some of the series. With these podcasts, go to the podcast web site and click on the show to immediately listen to it. A few of the podcasts are available through the iTunesU in the Apple iTunes store. Those podcasts are identified below with iTunesU. These will not appear in the search window if you look in the Apple iTunes Podcast page. You need to select the iTunesU library instead.

Using iTunes makes subscribing process easier for the podcast series. If the iTunes name appears in the podcast title line, go to the iTunes web site after you have downloaded the software to your computer (available for free from http://iTunes.com). Type the name of the podcast into the search window within iTunes and a window will open with information about the podcast. Simply click on the “subscribe” button within this window and the podcast series is automatically downloaded to your iTunes library account. New ones are automatically posted in the future. If you use another subscription service other than iTunes, or if the podcast show is not listed in the iTunes directory, you may need to enter the “subscription link” address by copying this link URL into your podcasting software (like iTunes, Juice, iPodder, or other RSS radio podcast client). This link is different than the URL for the web page.

Click on this link to download the my directory of favorite history podcasts you can subscribe for free through Apple iTunes. These should also be available through the Google Play Store as well.

Prerequisite Approach to Learning Assistance: Developmental-Level Courses, Part Four

The following is an excerpt from my book, "Access at the crossroads" described in the left-hand column.

A learning assistance approach that bridges the prerequisite acquisition approach of this section and the concurrent acquisition approach in the next is to place developmental courses in learning communities. To overcome disconnection that sometimes occurs for students in developmental courses with subsequent college-level courses in the academic sequence, some institutions place these courses in learning communities, integrating them with other college-level introductory courses (Malnarich and others, 2003). For example, a reading course might be paired with a reading-intensive course like introduction to psychology or world history. A rigorous study explored the impact of these learning communities. At Kingsborough Community College (part of the City University of New York), students scoring low on admission tests for English were placed in a learning community that included a developmental English course, a course in health or psychology, and a one-credit orientation course. Using a randomized trial that placed students in this learning community or a control group, the students in the experimental group experienced higher outcomes—enrolling in more courses, passing more classes, earning more college credits, and earning higher English test scores needed for a college degree (Scrivener and others, 2008).

Prerequisite Approach to Learning Assistance: Developmental-Level Courses, Part Three

The following is an excerpt from my book, "Access at the crossroads" described int he left-hand column.

Several reasons are possible why analysis of developmental courses sometimes yields mixed or negative results. As stated earlier about remedial courses, it is unreasonable to expect that years of inadequate education or ineffective student effort in high school can be overcome by a single developmental course. A second reason may be a basic flaw in research design. Previous national studies (Bailey, 2009; Kulik, Kulik, and Schwalb, 1983; Roueche and Roueche, 1993, 1999) did not add variables to their analyses concerning attributes of the developmental courses and contexts in which they were offered. They did not have the ability to sort out poorly managed, average, or well-managed programs. When student data from all institutions are aggregated, it is not surprising to find inconclusive results. A finer level of analysis is needed for this complex issue. The only national study on developmental courses was sponsored through the Exxon Foundation in the late 1980s; it found these courses effective when they observed best practices and poor results for those that did not (Boylan, Bonham, and Bliss, 1994).

The bottom line is that more careful and detailed research is needed to understand developmental courses and the variables that affect their effectiveness. Proponents and opponents of developmental courses call for more research in this area (Bailey, 2009; Boylan, Saxon, Bonham, and Parks, 1993). As the most vexing and controversial element of learning assistance, this issue demands careful and detailed national study. It is one of the recommendations for action listed in the final chapter of this report.

Prerequisite Approach to Learning Assistance: Developmental-Level Courses, Part Two

The following is an excerpt from my book, "Access at the crossroads" described in the left-hand column.

Sometimes students who enroll in these classes feel disconnected, perhaps because of the administrative location of the remedial or developmental course. No uniform pattern exists for location of these credit courses across the United States. At some institutions, the courses are taught in the academic departments of mathematics, psychology, or writing. At other institutions, the courses and other learning assistance activities are clustered in a separate academic or administrative unit in the institution (Boylan, Bonham, and Bliss, 1994).

A review of the professional literature identifies developmental courses as the most controversial and contested element of learning assistance. They have ignited fierce public debates between supporters and opponents. As described in one of the contemporary controversies, opponents of these courses question colleges dealing with learning competencies that should have been met while the student was in high school. With scarce funds for postsecondary education, spending money on instruction of remedial and developmental courses appears to duplicate efforts by the high school and waste precious resources. Another issue that critics raise with these courses is their effectiveness.

Although a review of the ERIC database and the professional literature reveals institutional studies affirming the efficacy of developmental courses, few national research studies are available of developmental courses. Older national studies found when developmental courses are offered separate from other learning assistance activities, the results are sometimes inconclusive (Kulik, Kulik, and Schwalb, 1983; Roueche and Roueche, 1993, 1999). Bailey (2009) analyzed these courses with a national dataset and found them ineffective. Among his recommendations were more research on these courses and use of more noncredit learning assistance services such as peer study groups.

Prerequisite Approach to Learning Assistance: Developmental-Level Courses, Part One

The following is an excerpt from my book, "Access at the crossroads" which is described in the left-hand column.

These courses, in contrast with remedial courses, focus on students’ strengths, develop both cognitive and affective domains, and build skills necessary for success in college-level courses. Remedial courses look to the past and focus on acquiring the skills and knowledge that should have been obtained while in high school; developmental courses look to the future and the skills needed for success in college. Typical developmental courses include intermediate algebra, college textbook reading, learning strategies, and basic writing composition. These courses count toward meeting financial aid requirements and often receive institutional credit. About 10 percent of institutions allow them to fulfill graduation requirements (National Center for Education Statistics, 2003).

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2003), two-year public institutions are the most common providers of developmental courses, with 98 percent offering them in one or more academic content areas. Eighty percent of public four-year institutions offer them. At private two-year institutions, the rate is 63 percent; it declines to 59 percent at four-year private institutions. The trend for these courses is relatively stable over the 1990s (National Center for Education Statistics, 1991, 1996, 2003), except for a steeper decline at public research universities (Barefoot, 2003).

Developmental courses are placed in the category of prerequisite acquisition approaches, because at most colleges students must successfully complete them before they are allowed to enroll in the next course in the academic sequence. For example, if the student scores low on college or institutional entrance exams in mathematics and is placed in intermediate algebra, he or she must successfully complete this course before being allowed to enroll in college algebra. Like for remedial courses, a student might be enrolled in a single developmental course during the academic term while all the other courses are college level, which is why students who are enrolled in these courses are not called “developmental students.” Most students who enroll in these courses do so only in one academic content area (National Center for Education Statistics, 2003). Although they need development in one academic content area, they are college ready or advanced in other areas based on college or institutional entrance exams.

Prerequisite Approach to Learning Assistance: Remedial Courses

The following is an excerpt from my book, "Access at the crossroads" described in the left-hand column.

These classes—basic reading, elements of English, and basic arithmetic—assume students possess fundamental cognitive deficits in need of remediation. These courses focus on academic content typically covered in middle school or early high school. At most institutions, these courses are a prerequisite before students may enroll in the next course in the academic sequence (Boylan, Bonham, and Bliss, 1994). Exit competencies of remedial courses generally prepare students for subsequent enrollment in a developmental course by teaching the needed skills and knowledge. For example, successful completion of a remedial course in fundamentals of mathematics provides a student with skills needed to enroll in an intermediate algebra course. Few students could complete the fundamentals of mathematics course and have a high chance of success in a college algebra course (Boylan, 2002b).

As described earlier in “History of Learning Assistance in U.S. Postsecondary Education,” four-year institutions offered remedial courses during the 1800s to meet the needs of students with poor or nonexistent secondary education (Maxwell, 1979). These remedial courses moved to the two-year colleges when they spread across the United States during the early 1900s (Cohen and Brawer, 2002).

Few national research studies concern the effectiveness of remedial courses. A common finding among these studies is that these courses must be more integrated into the culture of the institution and bundled with other learning assistance activities. If they are not, outcomes are mixed for most students (Kulik, Kulik, and Schwalb, 1983; Roueche and Roueche, 1993, 1999). It is unreasonable to expect to overcome years of inadequate education or ineffective student effort in high school with a single remedial course. Without the provision of remedial and developmental courses, however, students from impoverished backgrounds and poorly funded rural and urban schools have less hope for success in college.