This blog focuses on my scholarship in my five research projects: learning assistance and equity programs, student peer study group programs, learning technologies, Universal Design for Learning, and history simulations. And occasional observations about life.

History Simulations: Engaging Critical Thinking and Developing Multiple Perspectives from Other Cultures

My Global History Course Curriculum: Building Cultural Competency and Skill for a Diverse and Interconnected World

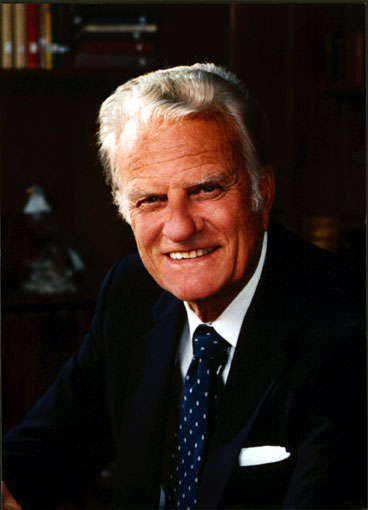

Dr. Rev. Billy Graham - "He is Risen"

In this podcast episode, we feature Reverend Billy Graham sharing a five-minute, low-key talk about importance of the Easter Story that he recorded in 1960 while on location in Jerusalem. There is a video of the same speech available through YouTube (click this link to watch it). Dr. Graham has retired from active preaching and lives in an assisted medical care facility. His wife passed a few years ago. I attended one of his revival meetings in a crowded Royals baseball stadium in Kansas City many years ago. It was an experience that I still remember today. Here is just a little bit of information about him. He was an active preacher and author for six decades. Dr. Graham sought to relate the Bible to contemporary social issues. He preached jointly with Dr. Martin Luther King at some crusades in the 1950s. Graham provided some of the bail money to release Dr. King when he was arrested after a civil rights demonstration. It is estimated the total audience at revival meetings, listeners on radio, and viewers on television of Dr. Graham’s messages exceeds two billion people. Click this link for a PDF from Wikipedia on the life of Dr. Graham.

In this podcast episode, we feature Reverend Billy Graham sharing a five-minute, low-key talk about importance of the Easter Story that he recorded in 1960 while on location in Jerusalem. There is a video of the same speech available through YouTube (click this link to watch it). Dr. Graham has retired from active preaching and lives in an assisted medical care facility. His wife passed a few years ago. I attended one of his revival meetings in a crowded Royals baseball stadium in Kansas City many years ago. It was an experience that I still remember today. Here is just a little bit of information about him. He was an active preacher and author for six decades. Dr. Graham sought to relate the Bible to contemporary social issues. He preached jointly with Dr. Martin Luther King at some crusades in the 1950s. Graham provided some of the bail money to release Dr. King when he was arrested after a civil rights demonstration. It is estimated the total audience at revival meetings, listeners on radio, and viewers on television of Dr. Graham’s messages exceeds two billion people. Click this link for a PDF from Wikipedia on the life of Dr. Graham.

Recommended History Podcasts

Click on this link to read a handout I prepared on podcasts related to history that I have subscribed for free through the iTunes Podcast service. I do not claim to listen to all the episodes obviously. However, I go through and select episodes of particular interest. I do make sure to download all episodes and went into the settings for my podcasts so that past episodes that are played do not automatically become deleted. Apple does that by default so that your hard drive is not becoming overloaded with media that you may not ever play again. While this is not a big issue with most audio podcasts, some video podcasts have enormous file sizes simply because it takes more room to provide them. Several of my personal favorites are the video podcasts from NASA. If you subscribe to the HD quality video podcasts, individual episodes can exceed 200 MB. Fortunately, most recent personal computers are increasingly providing standard hard drives of a terabyte or more. As a history teacher, I like to keep all the episodes for future reference. I think of them as my personal library like some people like to collect movie DVDs.

In 2013, Apple reported that a billion people world-wide have subscribed to a quarter-million podcasts in 100 languages, and that more than eight million episodes have been published in the iTunes Store thus far. Searching for podcasts through the iTunes Store can be a challenge. The following list is merely a sample of the history podcasts. They were enough of an interest to me to subscribe.

Many of the podcast shows can be subscribed to through iTunes, Google Play Store, and other mediasubscription services. Since I am most familiar with the Apple media ecosystem, the following podcasts are available through the Apple iTunes store. These are identified by the iTunes name appearing in the title line for the podcast. Formal subscription to the podcasts are not required for some of the series. With these podcasts, go to the podcast web site and click on the show to immediately listen to it. A few of the podcasts are available through the iTunesU in the Apple iTunes store. Those podcasts are identified below with iTunesU. These will not appear in the search window if you look in the Apple iTunes Podcast page. You need to select the iTunesU library instead.

Using iTunes makes subscribing process easier for the podcast series. If the iTunes name appears in the podcast title line, go to the iTunes web site after you have downloaded the software to your computer (available for free from http://iTunes.com). Type the name of the podcast into the search window within iTunes and a window will open with information about the podcast. Simply click on the “subscribe” button within this window and the podcast series is automatically downloaded to your iTunes library account. New ones are automatically posted in the future. If you use another subscription service other than iTunes, or if the podcast show is not listed in the iTunes directory, you may need to enter the “subscription link” address by copying this link URL into your podcasting software (like iTunes, Juice, iPodder, or other RSS radio podcast client). This link is different than the URL for the web page.

Click on this link to download the my directory of favorite history podcasts you can subscribe for free through Apple iTunes. These should also be available through the Google Play Store as well.

Study finds key criteria that determine college success for low-income youth

<Click on this link to download this report.>

<Click on this link to download this report.>

A five-year study by UC researchers that included a survey of California youth and interviews with more than 300 young adults about their interactions with educational institutions has identified the five key issues that matter most for understanding and improving college success for low-income students. The $7.5 million study, “Pathways to Postsecondary Success: Maximizing Opportunities for Youth in Poverty,” spotlights the importance of student voices, an understanding of student diversity, asset-based approaches to education, strong connections between K–12 and higher education, and institutional support for students. The study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and was issued by the University of California’s All Campus Consortium on Research For Diversity (UC/ACCORD) at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education and Information Studies (GSE&IS).

“Our study began in 2008, at the onset of a critical economic downturn—the Great Recession—which impacted education and the labor market in considerably complex ways,” said UC/ACCORD director Daniel Solórzano, co-principal investigator on the study and a professor of social sciences and comparative education at GSE&IS. “It was clear the recession had an effect on both colleges and students. Budget cuts slashed enrollments at campuses and decreased the resources for those already enrolled. Many low-income students faced even greater financial instability from the scarcity of work or sudden unemployment of family members. Therefore, at a time when students’ required additional support to stay on the path through college, the supports and conditions that are vital to their success were disappearing or overburdened on campuses.”

While “Pathways” reports on national data, the study focused on California, which has the largest number of community colleges (112). The vast majority of low-income students in California who pursue post-secondary education begin at community colleges.

Principal findings from the study include:

- Student voices matter: Education is a powerful force in the lives of low-income youth, and hearing what students say about their experiences is essential to understanding their educational pathways and outcomes. Financial difficulties, lack of available classes, transportation problems and a lack of availability of child care are obstacles to many low-income students’ success. Yet students reported that when they experienced caring educators and high-quality instruction in high school or college, this made a difference in their engagement and success in college.

- Diversity matters: Low-income youth are a diverse group, and understanding the similarities and differences in this student population enables administrators to better plan college success initiatives. In California, students of color make up the majority of community college enrollment, and many are the first in their family to attend college. Almost half (46 percent) of community college students are older, 54 percent work full-time and 16 percent are parents. “Common understandings of traditional college students may be less relevant as we plan for the growing number of community college students who are working full-time, raising families and have many responsibilities outside of school,” said Amanda L. Datnow, co-principal investigator on the study and a professor of education at UC San Diego. “These students are quickly becoming the majority, and we need to orient around their needs.”

- Assets matter: Report findings indicate that an asset-based approach helps education administrators tap into and foster students’ strengths in order to support college success. Low-income students enroll and often persist in college, although not always in traditionally defined ways. They arrive with high aspirations to do well and either finish their certificate program or transfer to a four-year college. Successful programs at the colleges affirm and tap into these assets.

- Connections between K–12 and higher education matter: High-quality K–12 schooling, combined with college preparatory resources, helps ensure college-going success for students. Nationally, 78 percent of low-income youth do not complete a college-preparatory curriculum in high school. In California, 85 percent of community college students require remediation in math and English to complete coursework they should have been taught in high school. Therefore, to ensure college readiness, better articulation between high schools and colleges needs to occur, and students need accurate information about enrollment practices and assessment procedures.

- Institutional supports and conditions matter: While funding cuts have resulted in reductions in mentoring programs and supports for students, financial difficulties, transportation problems and a lack of child care also frustrate many low-income students’ attempts to fulfill their goals. Low-income students are particularly dependent on financial aid to attend college, and information about resources—including academic and other services—must be integrated and streamlined to make the existing process less complicated and easier to access.

The multi-method study included the development of a monitoring tool to track educational opportunities for low-income youth. It also identified a set of indicators at the organizational level of community college campuses that support student success.

Challenges of First Generation College Students

Creating a College Culture

The initiative encourages students whose parents are low-income or who didn’t go to college to apply to at least one college or university. Started in 2005, it is funded by philanthropic foundations and coordinated by the American Council on Education, which represents the presidents of U.S. colleges and universities. High schools can customize their college application weeks to meet students’ needs, but all of them schedule time during school hours for seniors to submit applications, often aided by volunteers trained to answer questions.

Schools try to drum up publicity and enthusiasm by holding raffles for students who submit applications, handing out “I applied” stickers and urging teachers to decorate their doors with photos and pennants showing their own alma maters. The Oregon University System created a YouTube video featuring people’s responses when they asked them to explain—in five words or less—why students should apply to college. “It’s all about creating a college-going culture in our communities,” said Kate Derrick, a spokeswoman for the Tennessee Higher Education Commission, which coordinates the college application weeks in that state. “For us, it means for our students, it’s not a matter of if they’ll go to college, but where and recognizing that here in Tennessee, the jobs of the future will require college degrees.”

The American College Application Campaign began at a single high school in Siler City, N.C., and has since spread across the country. This year, about 2,000 schools in 39 states and the District of Columbia are participating. National College Application Week is Nov. 11-15 this year, but many schools hold their events earlier so students can take advantage of early action and scholarship deadlines. Many states have jumped in to help. In some, state employees coordinate the application drives, and some governors have signed proclamations to promote college application weeks.

The Burden of Being First

Bobby Kanoy, who directs the expansion of the campaign to new states, said that research shows the nation’s economy needs more college graduates. The percentage of 25- to 29-year-olds with at least a bachelor’s degree grew from 23 percent in 1990 to 33 percent in 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Even so, the U.S. isn’t producing enough graduates with the skills to thrive in the country’s evolving economy. “Unless we increase the number of students coming through the pipeline, we’re going to come up short,” of workers who are educated enough for the jobs of the future, Kanoy said. “If we come up short of people who can do these jobs… we either have to send the jobs offshore, or we have to import the talent. Matt Rubinoff, executive director of I’m First, an initiative of the Center for Student Opportunity, a nonprofit aimed at supporting first-generation college students, said that while low-income students in middle school aspire to go to college at the same rate as their higher-income peers, they don’t matriculate at nearly the same rate.

The barriers for first-generation college students may be big or small, real or perceived. Several high school counselors involved with the American College Application Campaign say that while most students have the desire to go to college, many first-generation students worry about not working to help support their families or fear taking on student loan debt, particularly in an uncertain job market. Others, lacking the support of someone at home who has been through the college application process themselves, may be deterred by something as seemingly insignificant as not knowing what to put down for “permanent address” on an application form, or by an inability to pay application fees, which are often waived by colleges for low-income students.

Scared to Apply

At Ottawa Hills High School in Grand Rapids, Mich., college adviser Gabe Pena, who was the first in his family to graduate from college, said that some students are drawn to work at one of the assembly-line jobs in southeast Grand Rapids, which beckon students with wages of $10 an hour. Other students avoid applications because they think they will have to fill out a lengthy application and write an essay, which is generally not true of community colleges. Pena said many students are excited to learn that the state offers a scholarship for many low-income students to attend community colleges. “The majority of kids want to go to college,” Pena said. “There’s this grand idea of college – it seems like something unattainable, but they want to get there. I help familiarize them with all the options.”

Laura Klinger, a college adviser at two high schools in rural St. Claire County, Mich., said that filling out a college application is often the easiest part of applying to college. But going through that process and receiving a notice of acceptance can boost a student’s confidence, she said, and motivate them to continue through the red tape of orientations, housing deposits and financial aid forms. “I think the value of having an adviser in the school is to try and help them with that process,” Klinger said. Skyler said some of the students from his high school who don’t go to college get involved with “bad stuff” like drinking, drugs and partying. “I probably would have lived at home,” he said, reflecting on how different his life might be today. “I probably wouldn’t have gone (to college) and a lot of things would be a lot different.”

San Jose State Efforts for First-Generation College Students

Also looking to expand the program is Art King, the university's associate vice president for student affairs. "Right now we only look at first-generation students when they come in, but they are first-generation students throughout their time at college," he says. "My hope is to have programs for second-year students, third-year students, and for fourth-year students, so each group gets appropriate resources and help."

Because the program is new and growing, there is not much long-range data on its effectiveness. Ms. Morazes is tracking the progress of participating students, including retention rates after the first year and progress toward declaring a major and earning a degree. She conducts evaluations before and after events to assess changes in students' knowledge of campus resources, their sense of belonging and connectedness, and whether they feel they are on track to earn a degree...."